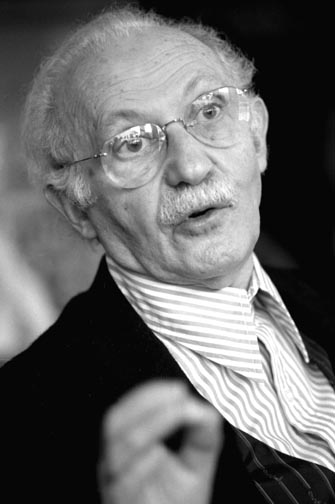

I became interested in Marcel Proust, for whose monumental masterpiece my blog is named, when I worked as an assistant to director Nicholas Ray at his acting and directing workshops at the Lee Strasberg Institute. In addition to the dynamic workshops of Nick Ray, I had the opportunity to sit in on a workshop given by the legendary Lee Strasberg, in which he chose a volunteer from the student audience and used the student to demonstrate the technique of emotional recall. That left an indelible impression on me, as the student was transported into another place, and all his senses were recreated – relived – to the most minute detail. The recollection of the student’s senses evoked the recall of the emotional state – as close as one could get to reliving the actual experience – it seemed a work of hypnotism on the part of Lee Strasberg.

Lee Strasberg

I had the further opportunity to personally experience such an intense emotional recall during Nick Ray’s workshops, using the techniques of Lee Strasberg combined with Nick Ray’s intensely personal directing style. I was able to relive a moment in my life, and felt that I was “there” for the period in which I was in the “spell.” Nick Ray and Lee Strasberg both had spoken about Proust in reference to the subject of the recollection of the senses and emotional recall, and about Proust’s famous madeleine and cup of tea, the taste of which unleashed memories in Proust resulting in several thousand pages and seven volumes which feature over 2,000 characters.

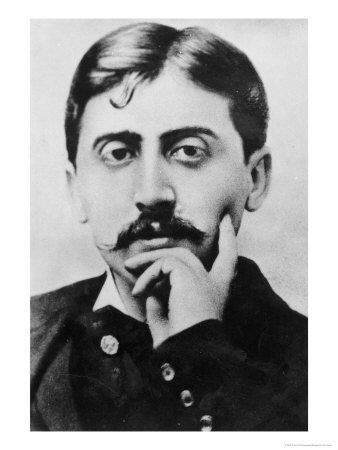

Marcel Proust

I was intrigued, and began reading “Remembrance of Things Past,” later retitled to the more literal translation “In Search of Lost Time.” I was tremendously captivated by the novel and read some of the volumes several times. It is my favorite book, the deepest and most profound book I have ever read – yet I am certain that I have not yet captured most of its meaning.

The book is not an easy read – it is admittedly tedious (but well worth it, at least it was for me) – and some of the sentences are so long that it is extremely hard to follow. I have been thinking for a while about a sentence I remember reading in “In Search of Lost Time” that was so incredibly long and I was eager for another read of it. I couldn’t possibly search for this sentence by perusing the seven volumes – that would likely take me years – but through the power of the internet, I tonight rediscovered Proust’s longest sentence – possibly the longest sentence in all of literature – and I am pleased to reprint this 958 word sentence in its entirety as a special bonus feature available exclusively (well, not really) here:

“Their honour precarious, their liberty provisional, lasting only until the discovery of their crime; their position unstable, like that of the poet who one day was feasted at every table, applauded in every theatre in London, and on the next was driven from every lodging, unable to find a pillow upon which to lay his head, turning the mill like Samson and saying like him: “The two sexes shall die, each in a place apart!”; excluded even, save on the days of general disaster when the majority rally round the victim as the Jews rallied round Dreyfus, from the sympathy–at times from the society–of their fellows, in whom they inspire only disgust at seeing themselves as they are, portrayed in a mirror which, ceasing to flatter them, accentuates every blemish that they have refused to observe in themselves, and makes them understand that what they have been calling their love (a thing to which, playing upon the word, they have by association annexed all that poetry, painting, music, chivalry, asceticism have contrived to add to love) springs not from an ideal of beauty which they have chosen but from an incurable malady; like the Jews again (save some who will associate only with others of their race and have always on their lips ritual words and consecrated pleasantries), shunning one another, seeking out those who are most directly their opposite, who do not desire their company, pardoning their rebuffs, moved to ecstasy by their condescension; but also brought into the company of their own kind by the ostracism that strikes them, the opprobrium under which they have fallen, having finally been invested, by a persecution similar to that of Israel, with the physical and moral characteristics of a race, sometimes beautiful, often hideous, finding (in spite of all the mockery with which he who, more closely blended with, better assimilated to the opposing race, is relatively, in appearance, the least inverted, heaps upon him who has remained more so) a relief in frequenting the society of their kind, and even some corroboration of their own life, so much so that, while steadfastly denying that they are a race (the name of which is the vilest of insults), those who succeed in concealing the fact that they belong to it they readily unmask, with a view less to injuring them, though they have no scruple about that, than to excusing themselves; and, going in search (as a doctor seeks cases of appendicitis) of cases of inversion in history, taking pleasure in recalling that Socrates was one of themselves, as the Israelites claim that Jesus was one of them, without reflecting that there were no abnormals when homosexuality was the norm, no anti-Christians before Christ, that the disgrace alone makes the crime because it has allowed to survive only those who remained obdurate to every warning, to every example, to every punishment, by virtue of an innate disposition so peculiar that it is more repugnant to other men (even though it may be accompanied by exalted moral qualities) than certain other vices which exclude those qualities, such as theft, cruelty, breach of faith, vices better understood and so more readily excused by the generality of men; forming a freemasonry far more extensive, more powerful and less suspected than that of the Lodges, for it rests upon an identity of tastes, needs, habits, dangers, apprenticeship, knowledge, traffic, glossary, and one in which the members themselves, who intend not to know one another, recognise one another immediately by natural or conventional, involuntary or deliberate signs which indicate one of his congeners to the beggar in the street, in the great nobleman whose carriage door he is shutting, to the father in the suitor for his daughter’s hand, to him who has sought healing, absolution, defence, in the doctor, the priest, the barrister to whom he has had recourse; all of them obliged to protect their own secret but having their part in a secret shared with the others, which the rest of humanity does not suspect and which means that to them the most wildly improbable tales of adventure seem true, for in this romantic, anachronistic life the ambassador is a bosom friend of the felon, the prince, with a certain independence of action with which his aristocratic breeding has furnished him, and which the trembling little cit would lack, on leaving the duchess’s party goes off to confer in private with the hooligan; a reprobate part of the human whole, but an important part, suspected where it does not exist, flaunting itself, insolent and unpunished, where its existence is never guessed; numbering its adherents everywhere, among the people, in the army, in the church, in the prison, on the throne; living, in short, at least to a great extent, in a playful and perilous intimacy with the men of the other race, provoking them, playing with them by speaking of its vice as of something alien to it; a game that is rendered easy by the blindness or duplicity of the others, a game that may be kept up for years until the day of the scandal, on which these lion-tamers are devoured; until then, obliged to make a secret of their lives, to turn away their eyes from the things on which they would naturally fasten them, to fasten them upon those from which they would naturally turn away, to change the gender of many of the words in their vocabulary, a social constraint, slight in comparison with the inward constraint which their vice, or what is improperly so called, imposes upon them with regard not so much now to others as to themselves, and in such a way that to themselves it does not appear a vice.” – Marcel Proust, “In Search of Lost Time”

* * *

Excerpt from a novel I have been writing called “White Sand Falling.”

(If you like this post and my blog please visit my facebook page here and click “like”)

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I love Proust, is one of my favorite writers. I always loved his long sentenses, a sign of a good writer who knows his language Sintaxis. But the sentence that you mention has several ( ; ) which in French ends a frase. The fact that he uses ( ; ) means that he is enumerating, but after the ( ; ) is a different sentence. The whole, forms a parafraph on the same subject, but does not make one sentense. They are several sentenses in what you printed.

Punctuation in the Latin Languages is very different of the one in English. I still cannot figure out the anglo Sintaxis, but I am not a writer, so I do not need it.

PS. I always read Proust in French. I am not French, I only love their language. I am a Spanish teacher. And I do not have many oportunities to have a nice conversation about Literature.